Telling truths through drawing, two brilliant books provide fresh windows on Thai self-image. A brilliant, accessible history, The Art of Thai Comics, reveals how Thai society has changed. And an award-winning graphic novel about the underclass, The King of Bangkok, depicts social realities that get sanitised in the public realm.

The power of comics is that people don’t take them seriously. Even as cartooning moves online, comic books remain a common sight and still form the biggest section of book shops and book fairs. There is a direct connection to the way Thai oral culture has been steeped in multi-panel visual stories with minimal text, from traditional temple murals and astrological guides to today’s illustrated fiction and captioned political memes.

The epitome of cute, cartoons have since the 1980s been consigned to the realm of mass entertainment, especially for children. But they are increasingly being recognised by aficionados as a legitimate art – and they reveal much about society. Their visual form is also a way to broach taboos that are hard to write directly.

Often regarded as throwaway ephemera, Thai comic books haven’t been preserved, archived, or researched properly. So it’s remarkable how a Bangkok-based Belgian, Nicholas Verstappen, has been able to track this underrated cultural source in such a comprehensive, landmark book, The Art of Thai Comics: A Century of Strips and Stripes (River Books, 2021, THB 1,495, in Thai and English).

Exceptionally well designed, this trove brings to light the great Thai cartoonists, their varied styles, and their innovations, such as giving physical form to ghost folklore and hybrids of foreign influences, imbuing Superman, or Elvis with a bricolage of fresh local meanings. One character even combined Mickey Mouse and Popeye in one chimeric body.

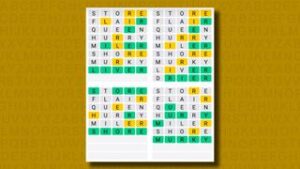

Foreign influences on Thai comics reflect wider effects on society from the dynamics of the era, starting with British satire, then including black and white movies, Americana, Japanese manga, and globalised youth culture. Through all these phases, Verstappen sensitively shows how cartoonists reflected the domestic situation, whether 1920s political caricatures, nation-building, militarist moralism, Cold War propaganda, devotional royal cartoons, or democratic diversity. All Thai life is here, from lore and lifestyles to business and beliefs.

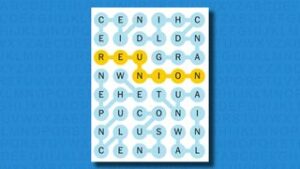

Cartoonists have often embedded critiques in their work – and even lauded masters like Hem Vejakorn and Prayoon Chanawongse have been censored by dictators of the day. While realists of the 1960s-70s For Life movement drew counter-culture tales of commoners, other cartoonists have promoted conservatism or been vehicles for propaganda. Verstappen ends with how Indie cartoonists have since the 2000s exploded the formats and visual styles of what comics could be, challenging the seniority system and the clichés of Thainess.

Verstappen includes so much that he had to limit the content to published comic books over one century. So he barely references the explosion of online political cartoon memes of the past decade, which have become so iconic in social media.

Into that gap rides a stunning graphic novel about the life and testing times of a motorcycle taxi driver, The King of Bangkok by Claudio Sopranzetti, Sara Fabbri, and Chiara Natalucci (University of Toronto Press, 2021, THB 1154), first published in their native Italian, and translated into Thai in 2019. Over 296 illustrated pages, we get a popular history glossed over by official and mainstream media.

The story is based on Sopranzetti’s decade of research. He documented the city life and backstory of ‘motosai ‘drivers in his thesis and book, Owners of the Map: Motorcycle Taxis, Mobility and Politics in Bangkok (2018). Through a remarkable collaboration, he turned his case studies into compound characters through the illustrations of Fabbri and the publishing skills of Natalucci to distill a complex phenomenon into an easy-to-read narrative.

A poor migrant to the capital, Nok, relates the key points of his life through cleverly selected flashbacks. We glimpse his hardscrabble upbringing, survival in exploitative jobs, marriage to the empathetic Kai, his role in political protests, and how he becomes a blind lottery seller.

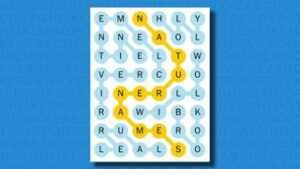

Colour is fundamental to experiencing the book. Each of the five chapters has a pair of hues that define its tone: cool blues for his harsh city arrival; earth tones for the warmth of family, monkshood, and marriage; acid pink and cyan for his druggy interlude working on Koh Pha-ngan; warm green and russet for the settled prosperity of the Thaksin years, when taxi bikers gained official recognition; then red and yellow clashing at the book’s climax.

The chapters open with ingenious scenes showing how the sightless Nok navigates the city’s rough edges via sound, with scenarios gleaned from interviews with blind Thais. While these pages are in black and white, coloured ‘windows’ appear at angles between Nok and the sources of urban noises, which are also conveyed by onomatopoeic words jingling at those places on the page. In a passage about how the rain heightens his senses, the colours wash more widely across the scene.

The level of craft is meticulous. Every small detail of fashions, products, advertising, and design is accurately sourced from a vast archive of images, divided by era. This is popular history at its most vivid.

The pivot points of Nok’s life deliberately coincide with the political upheavals that form a parallel narrative. It culminates in the violent crackdown on the 2010 protest by the Red Shirts, and their subsequent feeling of betrayal by Thaksin. Ultimately, this book gives a humane face to the brutal machinations of recent Thai history.

A theme throughout is sight, from Nok’s physical blindness through Buddhist insight and the realisation of family responsibilities to political awakening. The title of the Thai translation is Ta Sawang (Eyes Brightened) from a slang term for how ordinary Thais have come to see through the nationalist myths. Despite tackling uncomfortable topics, it sold well in Thai and won the Notable Book Award given by 60 Thai publishers. Its English translation, which won America’s 2022 Best Nonfictional Graphic Novel PROSE Award, brings this unique book to a global audience.

Together these two breathtaking books prove how cartoons deserve to be rehabilitated from the neglected margins to the forefront of literary art. And they place the stuff of ordinary life at the centre of Thai history.

Syndicated by River Books

This article relates to a chapter in Philip Cornwel-Smith’s latest book, Very Bangkok: In the City of the Senses. It is the long-awaited follow-up to Philip’s influential bestseller, Very Thai: Everyday Popular Culture. Both books are available from leading retailers and direct via the publisher at River Books.

FOR MORE:

Very Thai https://www.verythai.com

Very Bangkok https://www.verybangkok.co

Philip Cornwel-Smith https://www.philipcornwel-smith.com (coming soon)

River Books Shop https://www.facebook.com/riverbooksbk/?ref=page_internal